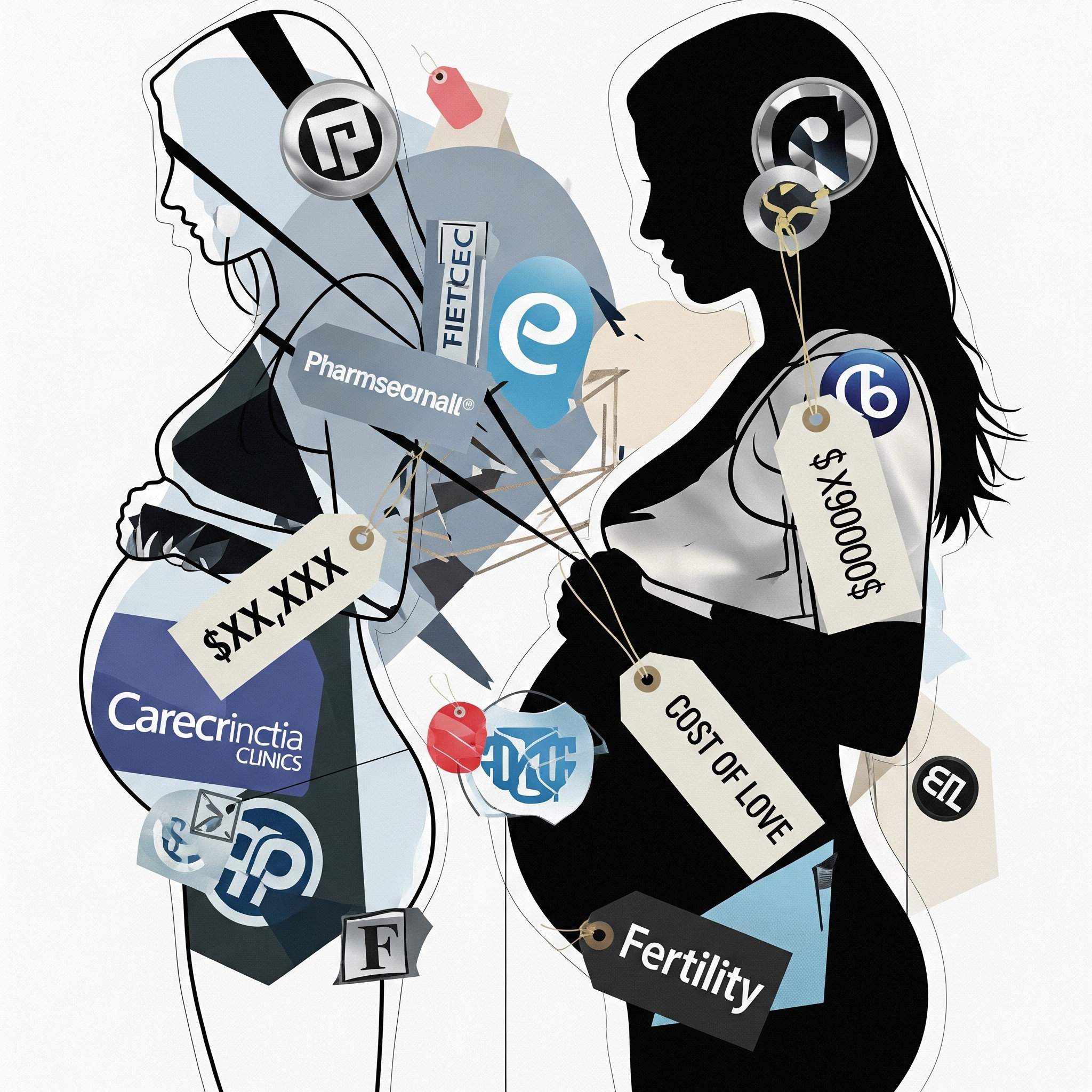

The Commodification of Motherhood: A Critical Look at the Surrogacy Industry

When we consider human progress, we have a curious habit of celebrating certain advancements without first inspecting the backstage machinery. Surrogacy, the practice of a woman carrying a child for another person or couple, is one such act. It is often lauded as a triumph of reproductive technology, a compassionate solution for those struggling with infertility, and a beautiful act of selfless giving. But a closer look, peeling back the layers of feel-good marketing and celebratory media coverage, reveals a troubling reality. This is not about celebrating families, it is about the uncomfortable truth that a woman's body has been formally enshrined as a commodity, her biology an asset to be leased, and her emotional and physical labour a service to be bought and sold.

The language surrounding surrogacy is a linguistic masterpiece of obfuscation. "Gestational carrier," "surrogate mother," "intended parents" - these terms are designed to sanitise the transaction, to distance us from the fundamental reality of a woman being paid to be pregnant. This is a deliberate process of dehumanisation, a way to make the act of renting a woman's womb sound like a simple business transaction. As the philosopher Elizabeth Anderson argued in her seminal 1990 paper, Is Women’s Labour a Commodity?, surrogacy exemplifies the corrosive effects of a market-driven approach to human reproduction. Anderson posits that it treats a woman's labour as a fungible commodity, ignoring the deep emotional and psychological bond that forms during pregnancy. In this brave new world, the female body is not a site of creation, but a site of production.

The process, and the money, creates a clear power imbalance. The "intended parents" hold all the cards, and the surrogate is often from a lower socio-economic background, seeking to improve her financial situation. This is not a voluntary arrangement between equals, but a contract-based transaction where one party's biological and emotional assets are at the disposal of another's financial power. A 2018 study by the Centre for Bioethics and Culture explored the demographics of surrogates in the United States and India, finding that a significant number of women were driven into the practice by economic desperation. The funny thing about "choice" is that it’s often a luxury. If your "choice" is between a surrogacy contract and financial precarity, how much of a choice is it really?

The true cost, however, is not just financial; it's psychological. The medical establishment, in its eagerness to facilitate these arrangements, often minimises the emotional impact of carrying and then relinquishing a child. The surrogate is often encouraged to maintain an emotional distance, to see the foetus not as her own, but as a "product" she is delivering. This can lead to severe psychological trauma and grief, a reality often ignored in the glossy brochures of surrogacy agencies. The academic Susan Bordo has long argued that this separation of body and emotion is a hallmark of patriarchal thought, and surrogacy is perhaps its most chilling manifestation. It demands that a woman override her own biological and emotional instincts for the benefit of another.

And what about the children? The very individuals for whom this process is supposedly undertaken? They are born into a transactional arrangement, not a natural family dynamic. Their existence is a result of a legal contract, not a spontaneous act of love. This raises profound ethical questions about identity, belonging, and the nature of parenthood. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child , adopted in 1989, states that a child has a right to know and be cared for by their parents. In surrogacy, the birth mother is legally and emotionally erased from the child's life, creating a foundational void that is rarely acknowledged. The child is, in effect, a product with a receipt, their origin story a footnote in a legal agreement.

We are told to see this as a progressive step, a liberation of motherhood from its biological constraints. But is it? Of course not, it is simply the latest, most sophisticated way to use and exploit women's bodies for the benefit of those with the means to do so. This is a question we must all address with intellectual honesty. The feel-good narrative of "making a family" must not blind us to the uncomfortable reality of what is being done. To see a woman's womb as a service for hire is not progress; it is an economic regression, a final, chilling step in the commodification of the human female. It's time to stop the applause and start asking some difficult questions, before the practice becomes so widespread that it is impossible to reverse.